Safeguarding Machine Learning Models: An Introduction to MIST

A paper review on MIST: Defending Against Membership Inference Attacks Through Membership-Invariant Subspace Training

Introduction

In the current landscape of rapidly evolving AI application fields, machine learning models have become integral to numerous applications, from voice assistants

The challenge for researchers and practitioners lies in developing robust defenses against these attacks without significantly compromising model performance. Traditional defense mechanisms often result in reduced accuracy as they aim to prevent the model from overfitting to the training data. In response to this challenge, a novel approach called Membership-Invariant Subspace Training (MIST)

This blog post aims to provide an overview of MI attacks and the MIST defense mechanism. We will begin by examining the fundamental concepts and mathematical principles underlying MI attacks. Then, we will explore how MIST offers an effective defense against these attacks, striking a balance between the critical needs of privacy and performance in machine learning models.

Our discussion will build upon existing research in the field, including seminal works on privacy-preserving machine learning and recent advancements in defense strategies against inference attacks. By the end of this post, readers will have a deeper understanding of the privacy challenges facing machine learning models and a clear insight into how MIST addresses these concerns.

Background and Previous Work

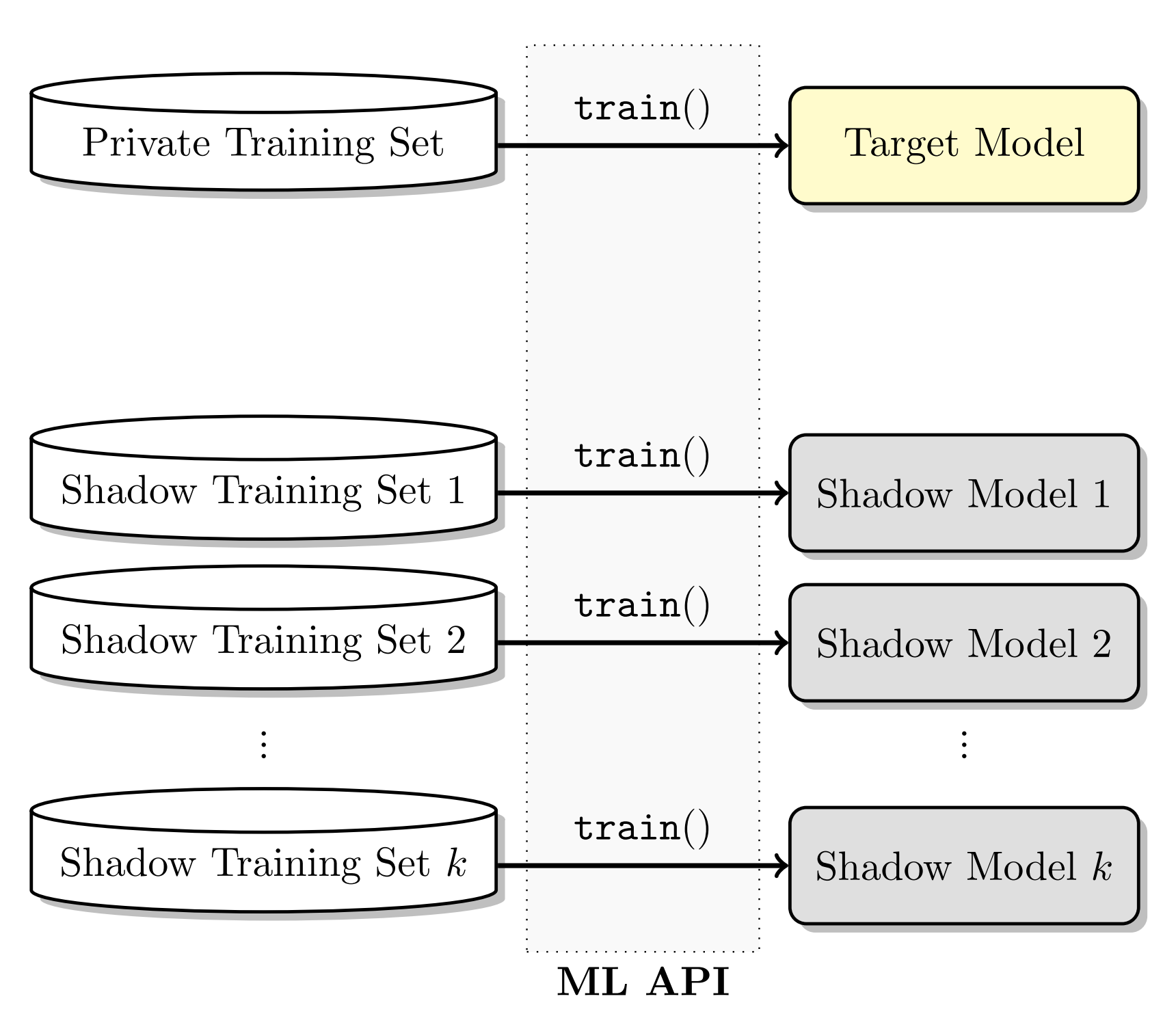

Membership Inference (MI) attacks were first systematically studied by Shokri et al.

One common defense strategy is differential privacy, which adds noise to the training process to mask the contributions of individual training examples. Abadi et al.

Despite these advancements, a fundamental challenge remains:

How can we efficiently learn membership-invariant classifiers to defend against MI for all vulnerable instances?

(Li et al., 2024)

This is where Membership-Invariant Subspace Training (MIST) comes into play. MIST leverages recent advancements in representation learning to focus on the instances most susceptible to MI attacks, offering a refined balance between privacy and accuracy.

In this blog, we will explore the mathematical underpinnings and intuitive concepts behind MI attacks and delve into how MIST effectively addresses these challenges.

Understanding Membership Inference Attacks

To appreciate the innovation behind MIST, it is crucial to understand the foundation of Membership Inference (MI) attacks.

Formulation of MI Attacks

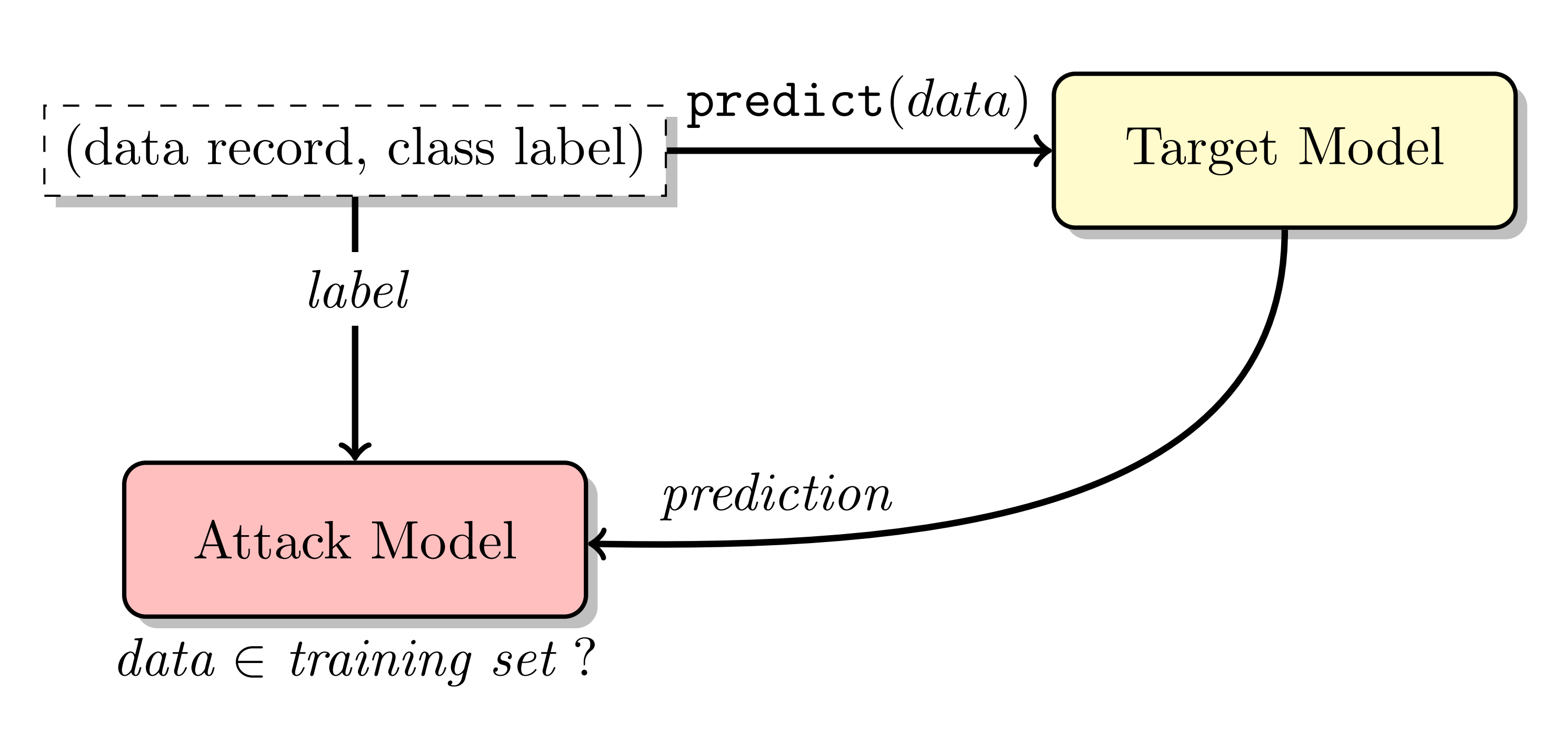

In a Membership Inference Attack, an adversary aims to determine if a specific instance $(x, y)$ was part of the training dataset $D$ used to train a machine learning model $F$. Formally, the adversary seeks to infer the membership status of an instance by analyzing the model’s behavior.

Consider a machine learning model $F$ trained on a dataset $D = {(x_i, y_i)}_{i=1}^{n}$. The model $F$ is optimized to minimize a loss function $L(F(x_i), y_i)$, which measures the difference between the model’s prediction and the true label. The goal of the training process is to reduce this loss for all instances in the training set.

However, this optimization leads to a critical vulnerability: instances in the training set typically exhibit lower loss compared to instances outside the training set. An adversary can exploit this difference by querying the model with an instance $x$ and observing the resulting loss $L(F(x), y)$. If the loss is significantly lower, the adversary may infer that $x$ was likely part of the training set.

Mathematically, an MI attack can be represented as:

\[\text{Infer}(\text{Membership}) = \begin{cases} \text{Member} & \text{if } L(F(x), y) < \tau \\ \text{Non-member} & \text{if } L(F(x), y) \geq \tau \end{cases}\]where $\tau$ is a threshold chosen based on the model’s loss distribution.

Intuitively, MI attacks take advantage of the fact that machine learning models are designed to perform well on their training data. When a model is trained, it “learns” the patterns and characteristics of the training instances, resulting in high confidence and low loss for these instances. Conversely, instances not seen during training generally result in higher loss as the model is less familiar with them.

Imagine a student who has studied specific questions for an exam. If the exact same questions appear on the test, the student will perform exceptionally well, similar to how a model exhibits low loss on training data. However, if new questions appear, the student’s performance may decline, akin to the model showing higher loss on non-training instances. An MI attack is analogous to an observer trying to determine if a particular question was part of the student’s study material based on the student’s performance.

Existing Defenses and Their Limitations

Existing defenses against Membership Inference (MI) attacks typically fall into two categories: regularization techniques and adversarial training. Each has its strengths and limitations.

1. Regularization Techniques

Regularization techniques aim to prevent the model from overfitting the training data, thus making it harder for an adversary to distinguish between training and non-training instances.

- Dropout: Dropout is a regularization method where a fraction of neurons is randomly dropped during training. This prevents the network from becoming too reliant on specific neurons, promoting a more generalized learning.

Limitation

While dropout can reduce overfitting, it also can degrade the model’s performance if not tuned properly. Additionally, dropout alone might not sufficiently obscure the distinctiveness of certain vulnerable instances.

- Label Smoothing: This technique involves modifying the training labels to be less confident. Instead of using a one-hot encoded vector, labels are smoothed to distribute some probability mass to all classes.

Limitation

Label smoothing can reduce the confidence gap between training and non-training instances, but it may also harm the model’s accuracy by making the learning process less precise.

- Differential Privacy (DP): DP adds noise to the model’s gradients or outputs to obscure the contribution of individual instances. It provides strong theoretical guarantees about the privacy of training data.

Limitation

The main drawback of DP is the trade-off between privacy and accuracy. High levels of noise ensure better privacy but significantly degrade model performance. Additionally, the implementation complexity of DP can be a barrier.

2. Adversarial Training

Adversarial training involves creating a separate adversary model that attempts to perform MI attacks during the training phase. The primary model is then trained to be robust against this adversary.

-

Adversarial Regularization: In this method, an adversary is trained alongside the primary model to identify whether instances are from the training set. The primary model is then penalized if the adversary successfully distinguishes training instances.

Limitation: Adversarial regularization can be effective but often leads to increased training complexity and time. Furthermore, it may not fully protect against more sophisticated MI attacks that the adversarial model wasn’t trained to simulate.

Limitations Across the Board

While these defenses offer some protection against MI attacks, they often come with significant trade-offs:

-

Accuracy Reduction: Many defenses reduce model accuracy because they prevent the model from fitting the training data too closely. This is especially problematic in applications where high accuracy is critical.

-

Computational Overhead: Techniques like adversarial training and differential privacy introduce additional computational overhead, making the training process more resource-intensive and time-consuming.

-

Inadequate Protection for Distinctive Instances: Most existing methods do not specifically address the differential vulnerability of training instances. They apply a uniform approach across all instances, which can leave the most distinctive and vulnerable instances insufficiently protected.

The MIST approach is designed to overcome these limitations by focusing on the most vulnerable instances and using a subspace learning framework to provide robust protection without sacrificing model accuracy.

In-depth Look at MIST

Conceptual Overview

The crux of MIST lies in addressing the differential vulnerability of training instances to MI attacks. Recognizing that not all training instances are equally susceptible, MIST focuses on protecting those with higher vulnerability, termed “distinctive” instances. This is achieved through a multi-phase process that blends subspace learning with counterfactually-invariant representations.

Subspace Learning and Counterfactual Invariance

- Subspace Creation:

- The training dataset $D$ is divided into multiple subsets $D_1, D_2, \ldots, D_k$.

- Independent submodels $F_1, F_2, \ldots, F_k$ are trained on these subsets. Each submodel $F_i$ learns from its respective subset $D_i$, creating a diverse subspace of models.

Mathematically, for each submodel $F_i$ trained on $D_i$: \(F_i = \text{Train}(D_i)\)

- Gradient Adjustment:

- To ensure that distinctive instances do not disproportionately influence the final model, gradient adjustments are performed.

- For each submodel $F_i$, the gradients are adjusted to align its predictions with the average predictions of other submodels.

Let $G_i$ denote the gradient of the loss function for submodel $F_i$: \(G_i = \nabla L(F_i(x), y)\) The adjusted gradient $\hat{G}_i$ is computed as: \(\hat{G}_i = G_i - \eta \sum_{j \neq i} (F_i(x) - F_j(x))\) where $\eta$ is a learning rate parameter.

- Averaging Submodels:

- The submodels are averaged to form the final model $F$.

- This averaging process ensures that the output on distinctive instances approximates the scenario where these instances are not included in the training, thereby reducing their vulnerability.

The final model $F$ is given by:

\[F = \frac{1}{k} \sum_{i=1}^{k} F_i\]

Mathematical Justification

The gradient adjustment step is pivotal in achieving counterfactually-invariant representations. By aligning the predictions of submodels, the influence of distinctive instances is diluted across the subspace. This reduces the variance in loss for these instances, making it harder for an adversary to distinguish members from non-members based on loss values.

The averaging of submodels further reinforces this invariance by ensuring that the final model’s behavior is a composite of multiple independent models. This composite nature helps in masking the presence of distinctive instances, thereby enhancing privacy protection.

THerefore, MIST represents a substantial advancement in defending against MI attacks, offering robust protection for vulnerable instances without the typical accuracy trade-offs. Future research could explore further optimizations and the application of MIST in diverse machine learning scenarios.